Robert Carlson’s Ultimate Story Structure Chart

- Posted: 6/1/21

- Category: Writing

- Topics: Seven Point System Three Acts Story Structure Writing Craft

What’s the Structure?

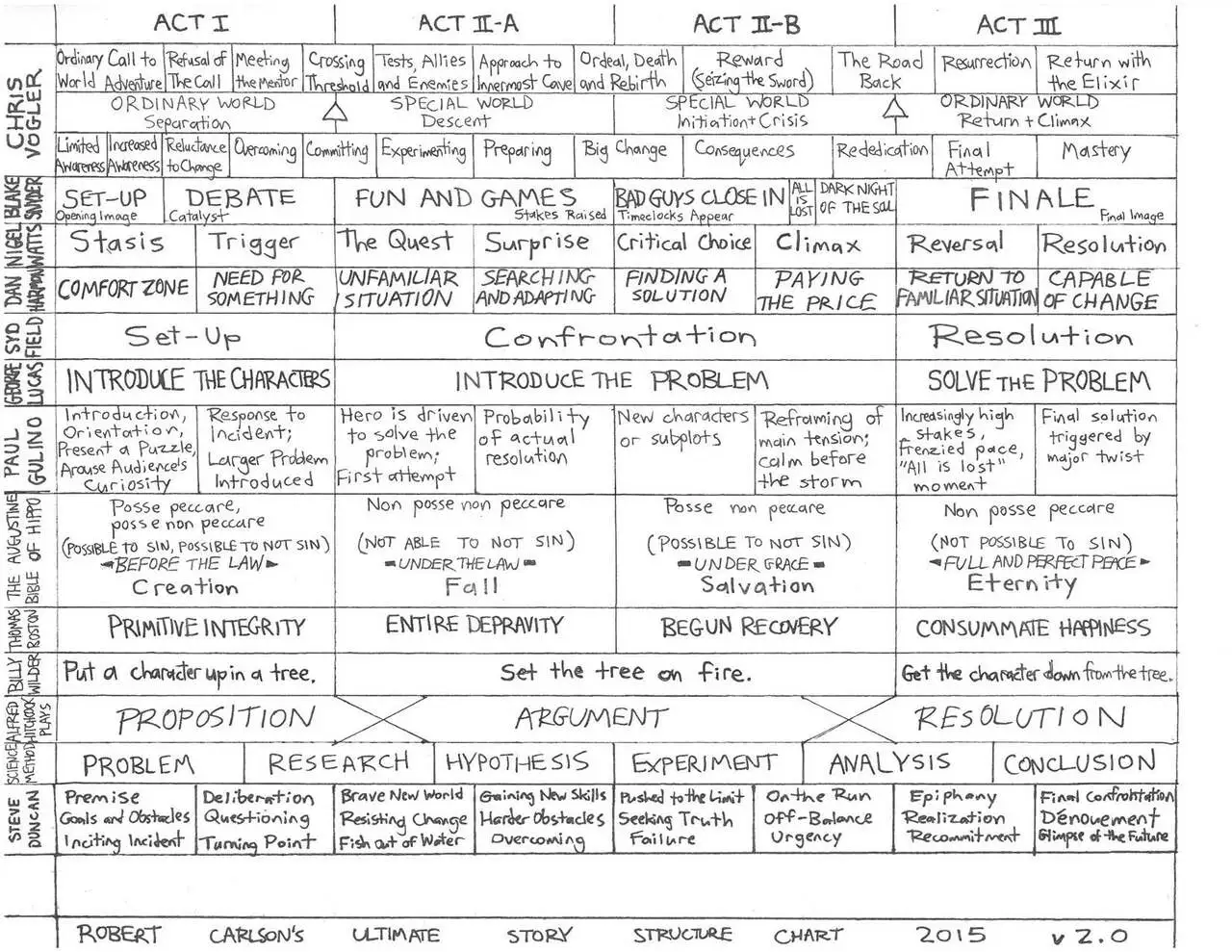

Robert Carlson created a summary chart of thirteen (13) story structure overviews. Here’s his diagram (saved from a comment at reddit).

Robert Carlson created a summary chart of thirteen (13) story structure overviews. Here’s his diagram (saved from a comment at reddit).

Across the top, note the Act I, Act II (parts A and B), and Act III divisions. Those are the ancient divisions. They go all the way back to the Greek philosopher Aristotle three and a half centuries before Christ.

Syd Field, George Lucas, Billy Wilder, and Alfred Hitcock–all of them masters of the visual art we call movies–adhere to that ancient structure.

I can remember learning to shoot target pistol and asking a High Master, the top echelon of precision-pistol shooters, how he does it? His answer was frustratingly simple. “Just aim at what you want, and then make the gun go ‘bang’ without messing that up.”

I suspect Syd, George, Billy, and Alfred are functioning at that same level. Their expertise functions at the level where they know all the rules, and they’re far more interested in when and where to break them, than when to comply.

For the lesser skilled such as I was when learning to punch holes in targets, I needed more detailed instructions.

For writing fiction, my favorite structure is the Seven Point system which unfortunately isn’t included by name in Rob Carlson’s summary chart. But is almost the same as that from Nigel Watts, the third name down.

Nigel divides the “Resolution” into two parts–“Reversal” and “Resolution”–whereas in the Seven Point system, it’s merely, “Resolution,” but other than that, they are almost identical.

But I will add that, after trying to apply that structure a couple of times, I need to tweak it. And while I agree that Act III needs to be divided, “Reversal” isn’t always indicative of what’s found in many stories. Instead, my preference is “Preparation” to suggest the protagonist getting ready to make his final assault. And that is then followed by “Resolution” where the confrontation finally happens. And then after that, [sigh], comes the “denouement,” the “happily ever after” paragraph.

Worse, none of these structures include what I now think of as the first point. I often find it on the first page, the first paragraph, and sometimes the very first sentence of a tale. It’s a Trigger Event and it changes the protagonist’s world such that he or she is forced to deal with it.

And everything that follows is a result.

This event happening right away is a fairly recent development. In older movies, you’ll see a different start. Movies used to start with several scenes that showed us the main character’s “normal world.” In those preparatory scenes, we might see the small town life where they live with “Gus” walking his rounds to deliver the mail, his stopping to chat with “Mike” as he picks up yesterday’s empty milk bottles and drops off full ones, and through someone’s curtained but open window, a table surrounded by kids having breakfast before school, Dad gulping his coffee with his tie unmade, and Mom bustling about to get everyone off to the next stage of their respective lives.

Then, something would happen. And because of it, the story would then head off in a different direction.

In recent movies, however, we get that Triggering Event right off the bat. Later, we might get a flashback to show us what used to be the “normal world,” but more often than not, we just hear a word or two about the way things used to be, and that’s all.

Seven to Ten Points, Depending

Here’s my current take on structure. I think it more accurately reflects what we see and read these days.

- Act I (Beginning, 25%)

- These three are often mushed together:

- Trigger Event – The Big Event that Changes Everything, but nobody knows what to do.

- Hook, if any – The Normal World (presented in flashback)

- Plot Turn 1 – The Trigger Event takes hold and we start to see just how the Main Character’s life is forever changed

- These three are often mushed together:

- Act II (Middle, 50%)

- Act II-A (first half of Act II)

- Pinch 1 – Bad Stuff Happens, Main Character Reacts to It

- Midpoint – Low Point in the Story. All Seems Lost.

- Act II-B (second half of Act II)

- Pinch 2 – The antagonist continues his plan, and even though the protagonist is creative with new ways to try and stop the bad guy, the bad guy’s plan continues inexorably forward.

- Plot Turn 2 – Another Big Event Changes Everything (Again) [Main Character’s attempts have failed but now he realizes he’s got to get the jump on the bad guy’s plan.]

- Act II-A (first half of Act II)

- Act III (End, 25%)

- Buildup – The protagonist begins formulating a plan, and commits to a mano-a-mano battle against the antagonist. He/she realizes no one else can do it. “It’s up to me,” he or she confides (to the reader or viewer).

- Climax – The final battle. Someone wins, and someone dies. For a happy ending, kill off the antagonist. For a trajedy, kill the good guy.

- Denouement – A final and very small description of what comes after. “And they lived happily ever after” is a classic example.

There are ten (10) minor bullets in the above list, although you might disagree about counting the Denouement as a “major point.”

And because the first three–Trigger, Hook, and Plot Turn 1–often get squished together, you could say that there’s often only seven.

But regardless of the count, what happens inside the protagonist is what matters, and that’s the basis of the (ancient) Three Act system.

Three Acts Unchanged

I’ve retained the Three Act containers for the simple reason that each of them shows the protagonist at a different stage of development.

In the first Act, the protagonist is living his/her normal life, expects the world to go on that way, and is flummoxed, befuddled, and flabberghasted when it is disrupted. Basically, he/she doesn’t know what to do about it, and the “winds of change” simply knock him or her about.

In Act II, the protagonist begins to resist, but only by using old solutions. Those efforts are disastrously unsuccessful, and by mid-point, the situation seems utterly hopeless. In the second half of Act II, the protagonist starts trying new things to defeat the evil forces, but is unsuccessful because the protagonist is one-step ahead. (The protagonist’s efforts are a day late and a dollar short.)

In Act III, the protagonist starts with an epiphany: “Only I can defeat the bad guy, and I can do it only by first outwitting, then second getting ahead of the protagonist’s plan, and then third only by physically defeating him.” In other words, the protagonist becomes an active planner, a schemer, more clever and conniving than the antagonist. He puts a plan together, assembles a team, collects the needed gadgets, sheds any old encumbrances, and takes full charge of the future. In a word, the bad guy is trumped.

Structure in Fiction

The key point in all this, and regardless of who’s system seems best, is that successful fiction almost always has some sort of structure, and that it is usually evidenced by how the protagonist changes from indifferent and unaware, to battered and bewildered, to trying to fight back but failing, and finally taking the bit between his teeth and duking it out with the bad guy/girl/force.

That evolution of the protagonist’s character is always there.

Applying one of the above structures to a story always improves the reader’s experience.

For students and practitioners of the craft of story-making, this summary chart is a marvelous creation. I tip my hat to Robert Carlson where ever he may be in the universe.